In the quiet ground of Seay Chapel Cemetery in Alexandria, Tennessee, rests the likely remains of Malachi “Mack” Berry, a man once enslaved in Smith County who at one time wore the uniform of the 17th Regiment, Company D, United States Colored Troops during the Civil War. His wife, Julia Roy Berry, a woman of dignity and quiet resilience, would spend decades in Alexandria raising their children and fighting—ultimately unsuccessfully—for recognition of her husband’s military service.

Born in Bondage: Malachi’s Early Life

Malachi Berry, whose name also appears in records as Malaki, Malichi, or Malachai, was born around 1839, likely in South Carolina or Tennessee. In the 1850 Federal Slave Schedule for James P. Berry(who appears to have immigrated from South Carolina), a male enslaved person aged 11 is listed—likely Malachi—alongside a 50-year-old woman who may have been his mother. By 1860, James P. Berry reported six enslaved individuals, including a 21-year-old male who fits Malachi’s profile.

Though exact records are lacking due to the nature of slavery, it is believed Malachi was held on land bordering Alexandria in DeKalb County. In April 1862, while still enslaved, Malachi married Julia Roy, another enslaved person living in Alexandria under Beverly Roy. The ceremony reportedly took place at the Roy home, officiated by Justice of the Peace Albert Bone/Bane. No formal record exists, as enslaved marriages were not recognized by law.

The War Years and Contested Service

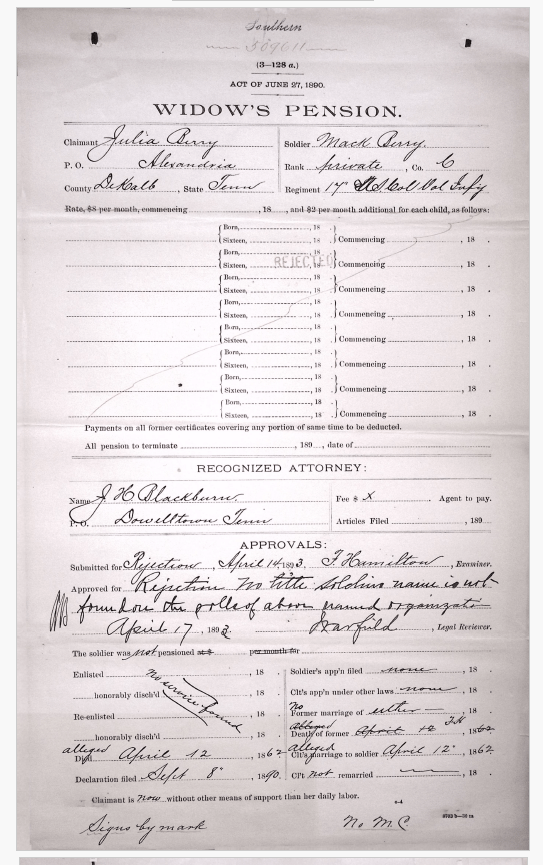

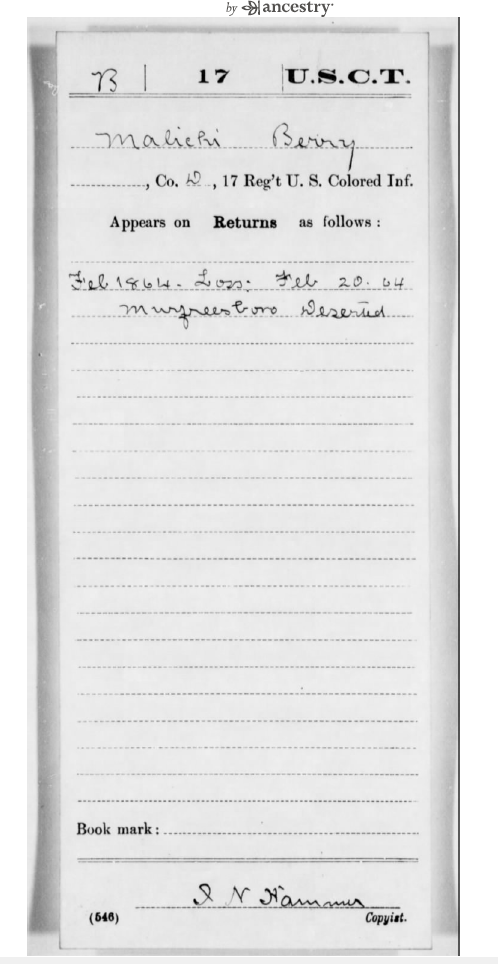

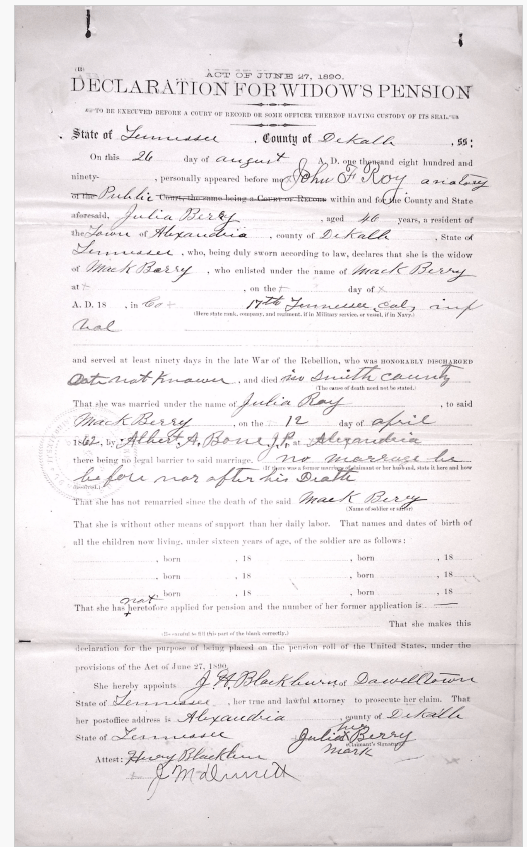

According to testimony given in a later widow’s pension application, Malachi joined the 17th Regiment, United States Colored Infantry, reportedly in Company C. Witnesses claimed he served under Captain Christopher Bateman, and that he had returned home on furlough before dying of illness. However, official records conflict: his name appears on a roll for Company D of the 17th USCT as absent in February 1864. Government officials later classified him as a deserter, which had his records been found would result in complicating the credibility of Julia’s claim.

Despite conflicting records, local testimony—including from John F. Roy, Jefferson Lawrence, and R.A. Lawrence—strongly supported Julia’s assertion that Malachi served and died during the war. Jefferson Lawrence stated that he and Malachi “grew up together,” suggesting a possible earlier connection between the Berry and Lawrence enslaving families.

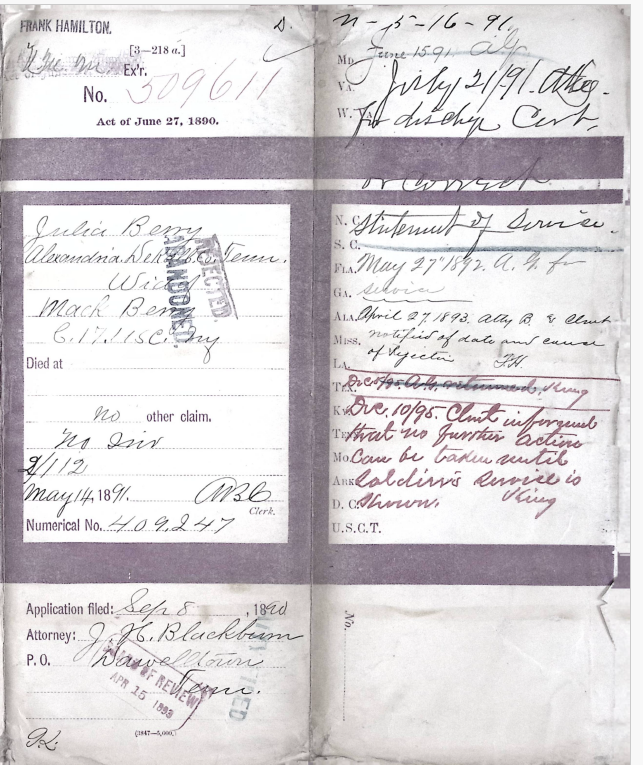

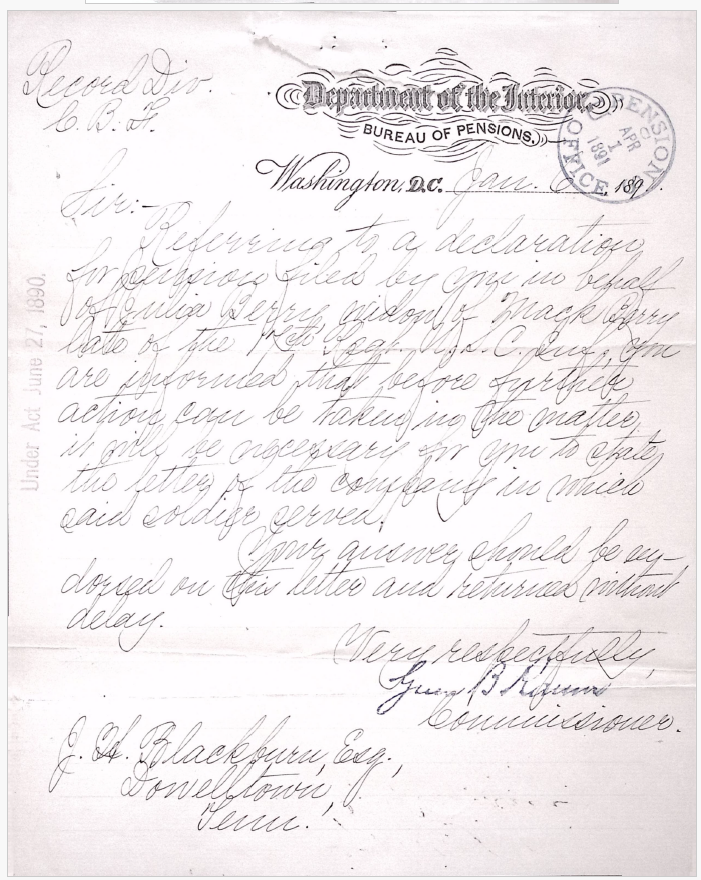

The service record for “Malichi Berry” on Fold3 confirms his association with the 17th Regiment, though the details remain murky. His widow’s pension application, filed in 1891 and final rejected in 1895, remains an important but heartbreaking document of post-war struggle for African American veterans and their families.

A Life of Resilience: Julia’s Story

Julia Berry (née Roy) was born on September 20, 1843. Her early life was spent in slavery, possibly in Warren County, Virginia, before she arrived in Tennessee with the Roy family. By 1860, she is believed to appear on the DeKalb County slave schedule as a 16-year-old girl, listed with a 35-year-old female—likely her mother—and a 10-year-old girl.

After Malachi’s death, Julia remained in Alexandria. The 1880 census shows her living on Main Street with daughters Elzora (Zora), Laura, and Harriet (Hattie), working as a servant. Her neighbors included John F. Roy, son of her former enslaver and witness on her pension application. She later lived with George Rollings, listed as her father in the 1900 census, though whether he was her biological father or a familial designation created by circumstance remains uncertain.

Julia raised her children and grandchildren alone. She applied for a widow’s pension in 1891, stating that her husband had served and died for the Union cause. Despite extensive testimony and four years of appeals, the government denied her application, citing a lack of documented proof.

By 1910, Julia had become a laundress and homeowner, still residing in Alexandria on Lebanon & Sandith Pike. She reported having had four children, only one of whom—Zora—was still living by that time. Julia Berry died on November 7, 1918. She is buried in Seay Chapel Cemetery, likely near her husband and their lost children, though no headstone exists to mark his grave.

Their Children and Descendants

Julia and Malachi Berry are believed to have had four daughters, however due to conflicting dates, all children may not be his, or dates may be wrong.

- Zora (Berry) Dowell (c.1863–1914), who lived into adulthood and left descendants.

- Maudaville Berry (c.1865–before 1891)

- Laura Berry (b. 1866 – d. before 1910)

- Harriet “Hattie” Berry (c.1868 – d. before 1891), who is believed to have been married to a Canary/Canardy Lawrence

The family’s records are scattered, and it is likely that some details will never be recovered. However, the census shows that by 1900, Julia was living with a multigenerational household of Dowell descendants, including her grandchildren.

A Legacy Waiting to Be Honored

The story of Malachi and Julia Berry represents more than one family’s journey—it illustrates the broader narrative of African Americans in Tennessee who sought freedom, dignity, and recognition in a post-slavery world that offered few certainties.

Malachi Berry may never receive a headstone or official military honors due to the conflicting records. Yet, in the testimonies of those who remembered him and in Julia’s unyielding pursuit of justice, his memory is preserved. Their lives are intertwined with the soil of Seay Chapel Cemetery and with the historical record of DeKalb County’s African American community.

As restoration efforts continue at Seay Chapel, and as genealogists, historians, and descendants reclaim these lost stories, may the legacy of Malachi and Julia Berry finally receive the recognition it so deeply deserves.

Research will continue on Julia’s beginnings, as it is highly suspect that the deed transactions, potentially naming her mother, and others that migrated with the Roy and Lawrence’s to DeKalb, and buried in Seay, may be noted there.

It is highly unlikely we will be able to obtain a Military Tombstone for Malaki, as the official record shows he deserted, and the likelihood of finding any proof of death that correlates to his absence is close to null. If you know any of the descendants of their daughter Elzora, who married into the Dowell’s, we’d be ecstatic to add more to their stories.

Sources:

- U.S. Federal Census (1850–1910), DeKalb and Smith Counties, Tennessee

- U.S. Civil War Pension File: Julia Berry, Widow of Malachi Berry (National Archives; reviewed via Gopher Records, June 2025)

- Fold3: Military Record for Malichi Berry, 17th USCT

- Tennessee State Death Records (1918), Julia Berry

- Find A Grave Memorial #123452303, Julia Berry

- Personal correspondence and research by Kristina Wheeler, 2024–2025, with verification and assistance from William Freddy Curtis

Leave a comment